Street art recorded protest and pandemic in real time. Researchers are trying to save it.

You can learn a lot about a place from its graffiti, stickers and tags, especially when all the museums are closed.

In May 2020, Todd Lawrence and Heather Shirey were taking pictures of graffiti focused on the coronavirus in Minneapolis when a police officer killed George Floyd just a few blocks away.

The two cultural historians from the University of St. Thomas had recently started taking pictures of the murals, graffiti, stickers and tags throughout the Twin Cities in an effort to preserve that work during a once-in-a-century pandemic. Their archiving, though, took on a new level of urgency when a police officer murdered Floyd and footage of the killing went viral, sparking anti-racist demonstrations in Minneapolis and throughout the world.

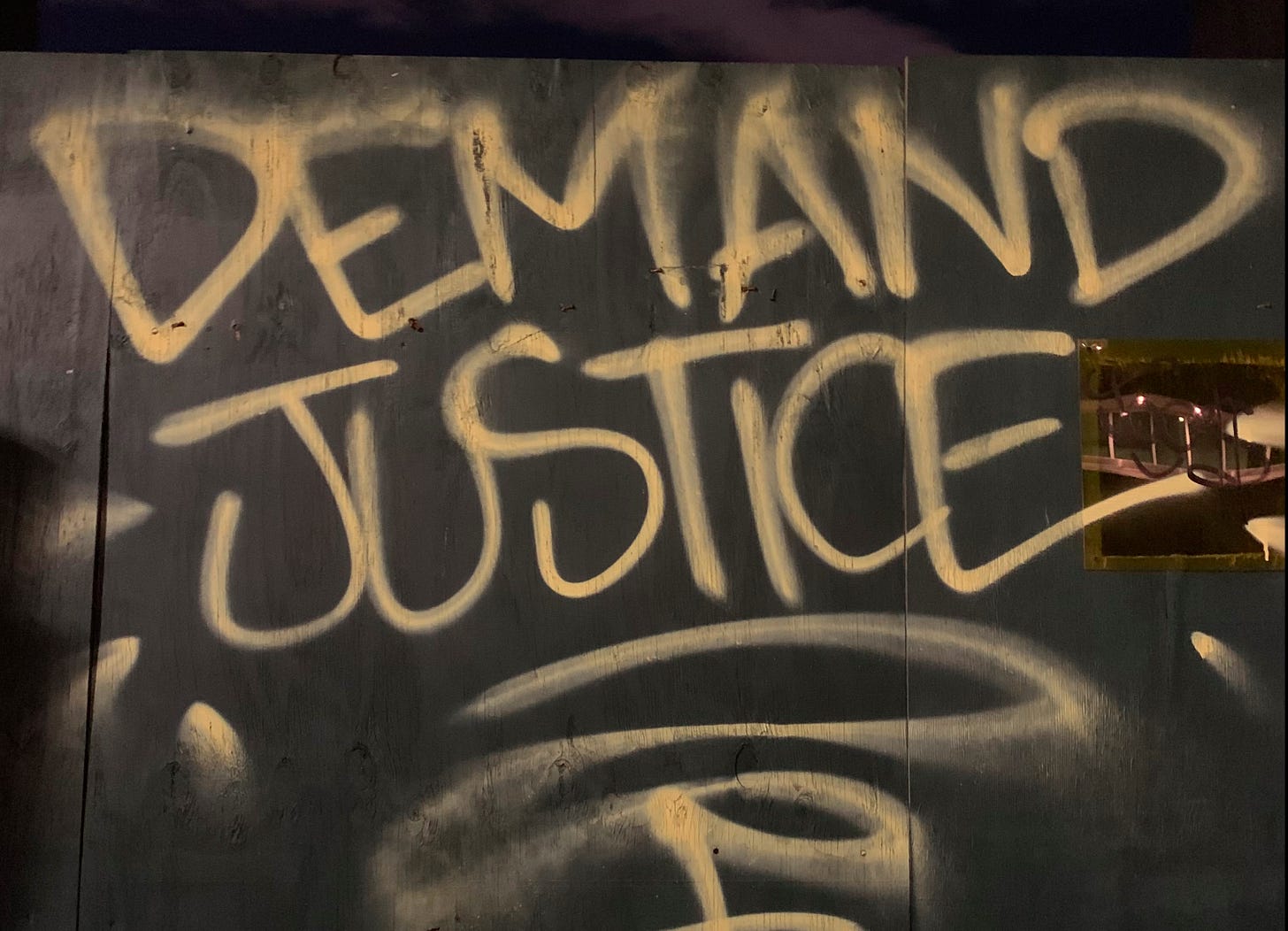

The movement had sparked the greatest proliferation of street art in recent memory, Lawrence says now, even if much of it was ephemeral, controversial and quick to be erased. At a time when the coronavirus was decimating communities of color, though, and with renewed attention on police brutality, street art represented a kind of live communication between neighbors.

“This was all happening a few blocks from my house and, when I went out in the mornings, there was art everywhere, tags everywhere and graffiti everywhere,” Lawrence told me during a recent call. “People had started to write on the boards that were up over broken windows. We realized right off the bat that this was the most art we’ve seen overnight, like instantaneously.”

An archive of all that conversation, the logic goes, will help activists, students and researchers more fully understand what it was like to live through a historic moment, particularly as many of the museums, concert halls and other hubs of shared cultural experience remained closed.

It’s not just in Minneapolis, though. Relevant street art will inevitably be visible during a short walk through New York City, where COVID-19 has killed more than 40,000 people, or Louisville, where plainclothes cops in March gunned down Breonna Taylor in the middle of the night.

“We realized that we really needed to document the response because there are of course miles and miles of plywood [in Minnesota] and elsewhere in the world that’s becoming this art gallery in the streets,” said Heather Shirey.

And the communication on those walls was changing really quickly. Right after some of the very intense conflict in St. Paul, there was graffiti that went up right around the areas where protestors were confronting police. There then was a lot of pushback against the protesters...We realized that was going away really quickly. It was cleaned up — or erased, to be more accurate, or silenced — and replaced with different messages. Sometimes a little tag that said BLM would be replaced with a big mural that said Black Lives Matter all around it. Sometimes the narrative would change, from something like “Abolish the Police” to “Midway Neighborhood Unite” so we were interested to see how this was changing over time.

Now, Shirey and Lawrence are urging members of the public to contribute to their databases, the George Floyd & Anti-Racist Street Art archive, and the COVID-19 Street Art Mapping project, to provide a public resource aiming to document the ways people are leveraging outdoor spaces to communicate. Contributors from throughout the world have submitted more than 800 pieces so far, ranging from simple “ACAB” graffiti to pathogen-inspired paintings.

The only rule: No advertising, or brand-sponsored commercials.

“We don’t see any value difference between the smallest piece of graffiti and a giant beautiful mural that took four days for a couple of people to put up,” Lawrence says. “We don’t want to overlook the stuff that many people see as insignificant, or that they might see as just vandalism.

“If you see something as a destruction of property that’s maybe more interesting to us, just because it is by definition a sort of criminal act,” he went on. “You then have to ask, ‘Well, what defines a criminal act in this moment?’ And, if it’s defined as a destruction of property, well, whose property is that? You have to ask what public property is, and who gets to make decisions about what happens there.”

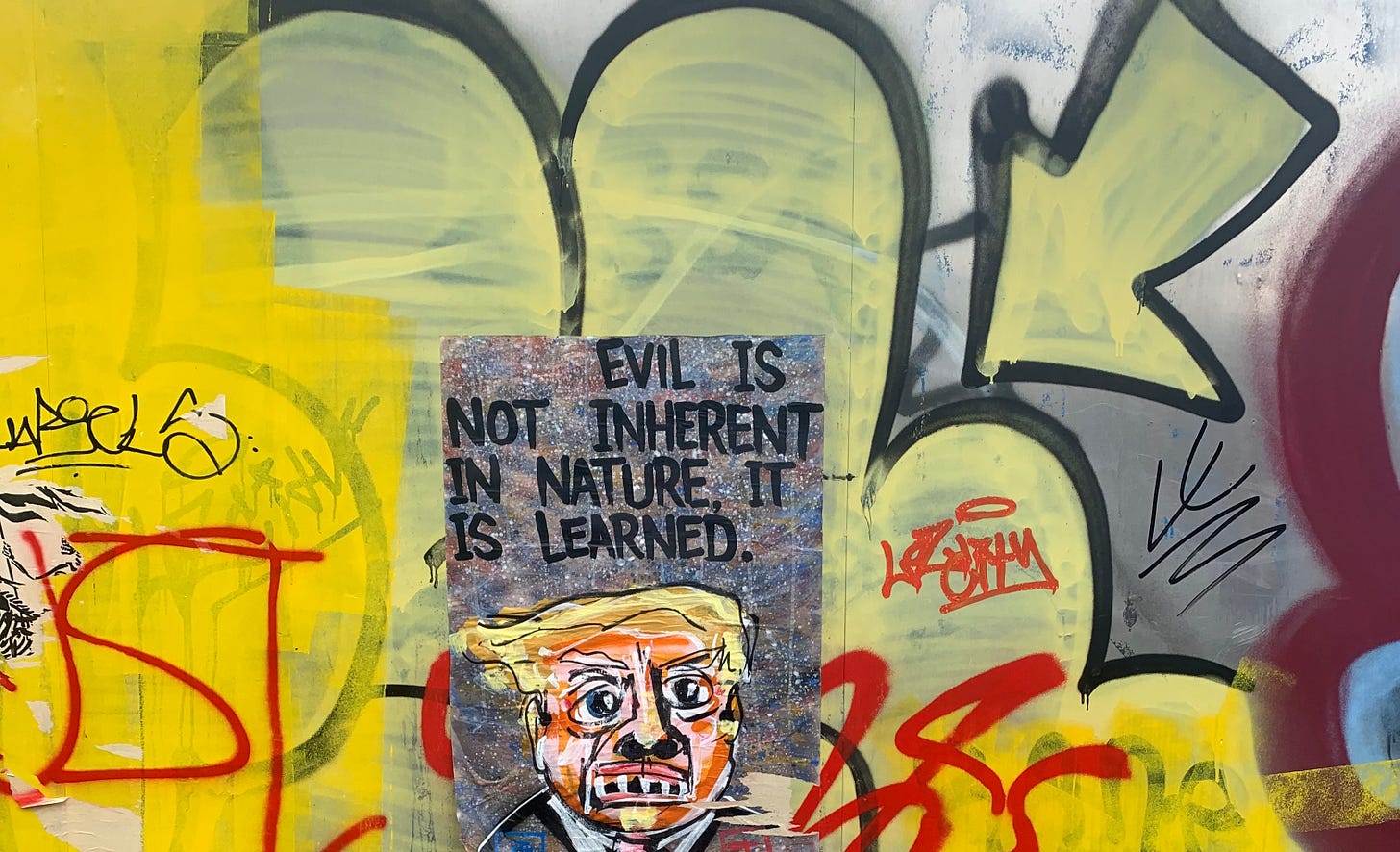

Art, advertising and political propaganda have merged “into a kind of collective funhouse mirror, instantly revealing indications about how a culture sees itself, as well as telling you about the tenor of discourse at any given time,” Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, co-founders of Brooklyn Street Art, a New York collective told me in an email.

Small, one-off handmade works are often “more labor intensive and less obsessed with multiple campaigns,” the BSA founders said. The existence of that work — typically made with stencils, wheat-pasted works, yarn, soldiered steel sculpture, wood, photocopies, illustrations, paintings, aerosol plaster, recycled garbage or light projections, according to Harrington and Rojo — is proof that a community of artists is responding to trauma, and reacting to the feeling of being “invisible or marginalized,” Harrington and Rojo said.

And the urgency behind much of that work is resonating more now than at perhaps any point in recent memory. Just ask Austin Zucchini-Fowler, a Denver-based artist who painted a series of tributes to medical professionals through the city last year. One series in particular, dubbed “Healthcare Angels,” went viral, attracting the attention of the New York Times and area medical workers.

“Whether its claiming space or someone showing their style or showing a different scene that impacts your perception of the world, there’s a beauty to all this,” Zucchini-Fowler told me. “All of it is an opportunity to publicly send a message.”

You can contribute to the George Floyd & Anti-Racist Street Art archive and/or the COVID-19 Street Art Mapping project by taking a picture of the art you see, and uploading it to either website. You can also follow the project on Twitter or Instagram.

recommended reading

The Biggest Thing Missing From Joe Biden’s Climate Plan - Plastic: Discouraging fossil fuel companies from extracting more oil and gas is just the beginning. [@dharnanoor]

I Feel Better Now: “The question of whether [therapy] apps are demonstrably effective at alleviating depression is less interesting than the question of why the market is so saturated with them in the first place.” [@jake_bittle]

How a Historian Got Close, Maybe Too Close, to a Nazi Thief: A new book relies on the word of a 6-foot-4, 300 lb. former Nazi who plundered art collections on Hitler’s behalf. This New York Times book review examines how the historian seemed to slip into the shadowy art world he was meant to be chronicling. [@nina_siegal]

The Pandemic Is Undermining Weather Monitoring: “Globally, many thousands of buoys, floats, ship-based sensors, and human observers supply weather forecasters with precious data about the conditions at sea.” The coronavirus is disrupting efforts to update and repair some of these networks, resulting in unreliable weather forecasts and questions about when data becomes unreliable. [@chrisbaraniuk]

Jon Krakauer on the 25th Anniversary of Into the Wild: Jon Krakauer says he’s done writing books. “I want to write less, and live more.” [@thepressboxpod]

Why British Police Shows Are Better: Part of the reason that shows like Broadchurch and Happy Valley are so compelling is because they function as modern day detective shows without relying on guns as a storytelling device. The lack of guns isn’t the only British-ism (see: widespread use of CCTV footage) but U.K. narratives also are distinctive because of “their refusal to wallow in grimness, instead stepping back to make room for emotions such as grief and guilt and faith and redemption in a manner not at all typical of American cop fare.” [@OrrChris]

one more thing

No More Normal is a semi-regular newsletter written by Jeff Stone. You can lend your support by subscribing, sharing with friends or suggesting ways to improve.