For all the ink spilled on a murder trial that took place in 1960, you’d think there was ever any question about who pulled the trigger.

There was never really any doubt that Dr. Bernard Finch and his lover, Carole Tregoff, had killed Finch’s wife, Barbara, resulting in a case that would dominate tabloid headlines for months, only to fade into obscurity.

In 1959, Dr. Finch, a 41-year-old surgeon and “serial philanderer” living in Los Angeles, was having an affair with Tregoff, his 22-year-old secretary. When the pair, both married, signaled their intent to leave their spouses and start a new life together, Barbara Finch hired a private investigator to follow her husband.

By proving adultery, the logic goes, Mrs. Finch stood to gain much of her husband’s fortune, worth a reported $6 million in today’s dollars.

After Barbara Finch filed for divorce, though, and won a court order to freeze her husband’s financial accounts, she was found dead in the family garage with a bullet between her shoulders.

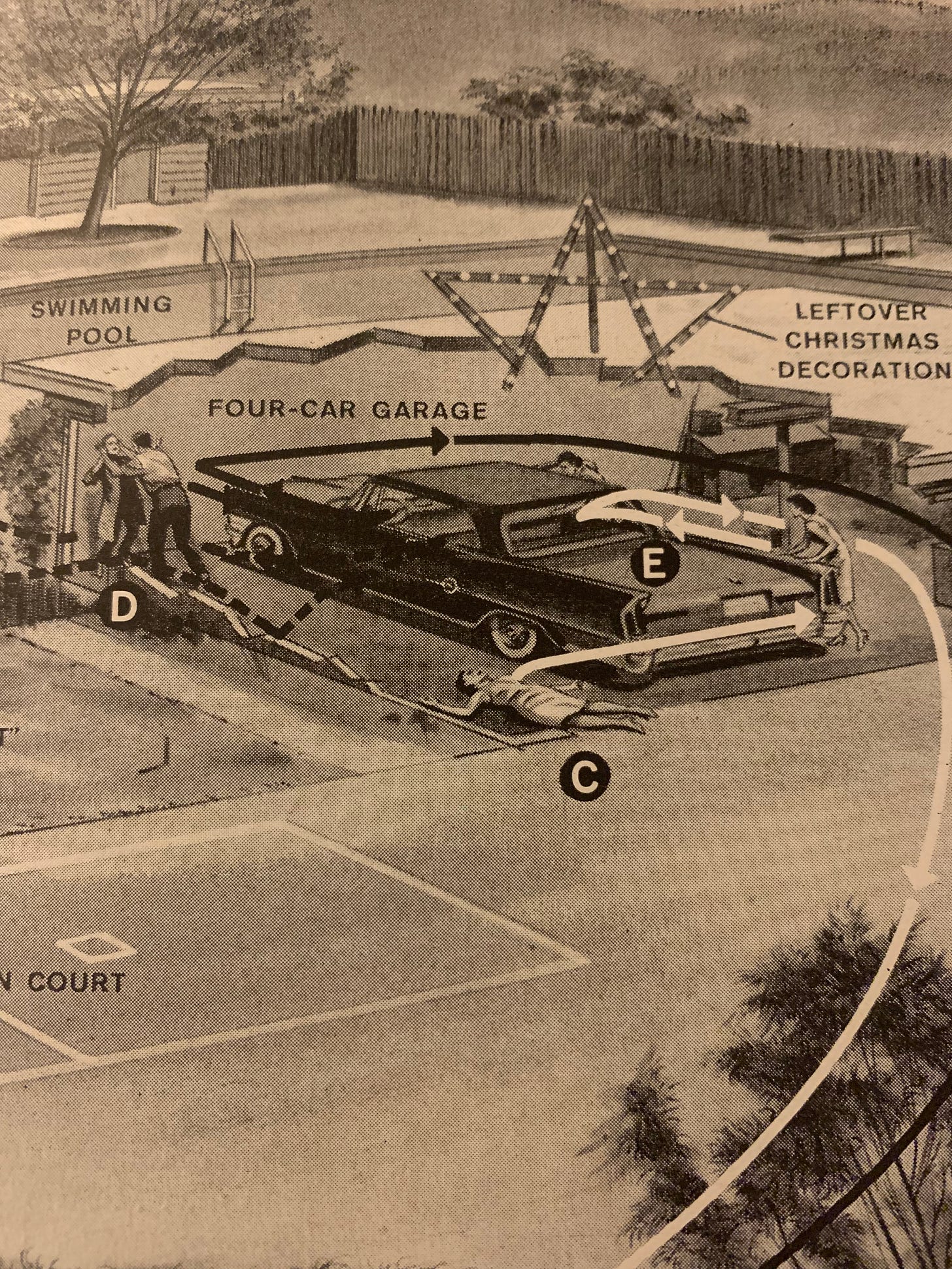

Very little of the tabloid coverage of the case still exists today. What remains, however, includes reporting from the trial indicating that Dr. Finch and Carole Tregoff were waiting in the bushes one night when Mrs. Finch arrived at home on 2750 Lark Hill Drive on the night of July 18, 1959. The family’s au pair, Marie-Anne Lindholm, testified that Finch had pistol-whipped his wife, then shot her in the back from six feet away when she tried to escape to a neighbor’s house.

Finch then ran off, leaving the 22-year-old Tregoff “cowering behind a bougainvillea bush, unseen by the police, the coroner, and the dead woman’s two children,” for six hours, until she made off unnoticed, per Los Angeles Magazine. Police caught up to Finch in Las Vegas within 24 hours, while Tregoff was arrested 10 days later.

The trial generated enough interest for Life magazine to devote eight pages of its Feb. 15, 1960 issue to the case, including a special report from celebrated British mystery writer Eric Ambler from inside the courtroom. Ambler was barely able to contain his excitement — or sexism.

The Finch-Tregoff trial is in the rich, rococo tradition of the great American courtroom dramas. It has everything which that tradition demands. It has love, lust, passion, hate, greed, adultery, plots, counterplots, sensational disclosures. It has a cast of characters which includes beautiful blondes, beautiful brunettes, Hollywood “personalities,” hired “killers,” private eyes and Perry Mason-like attorneys. Los Angeles has given its best — and is now making the most of it.

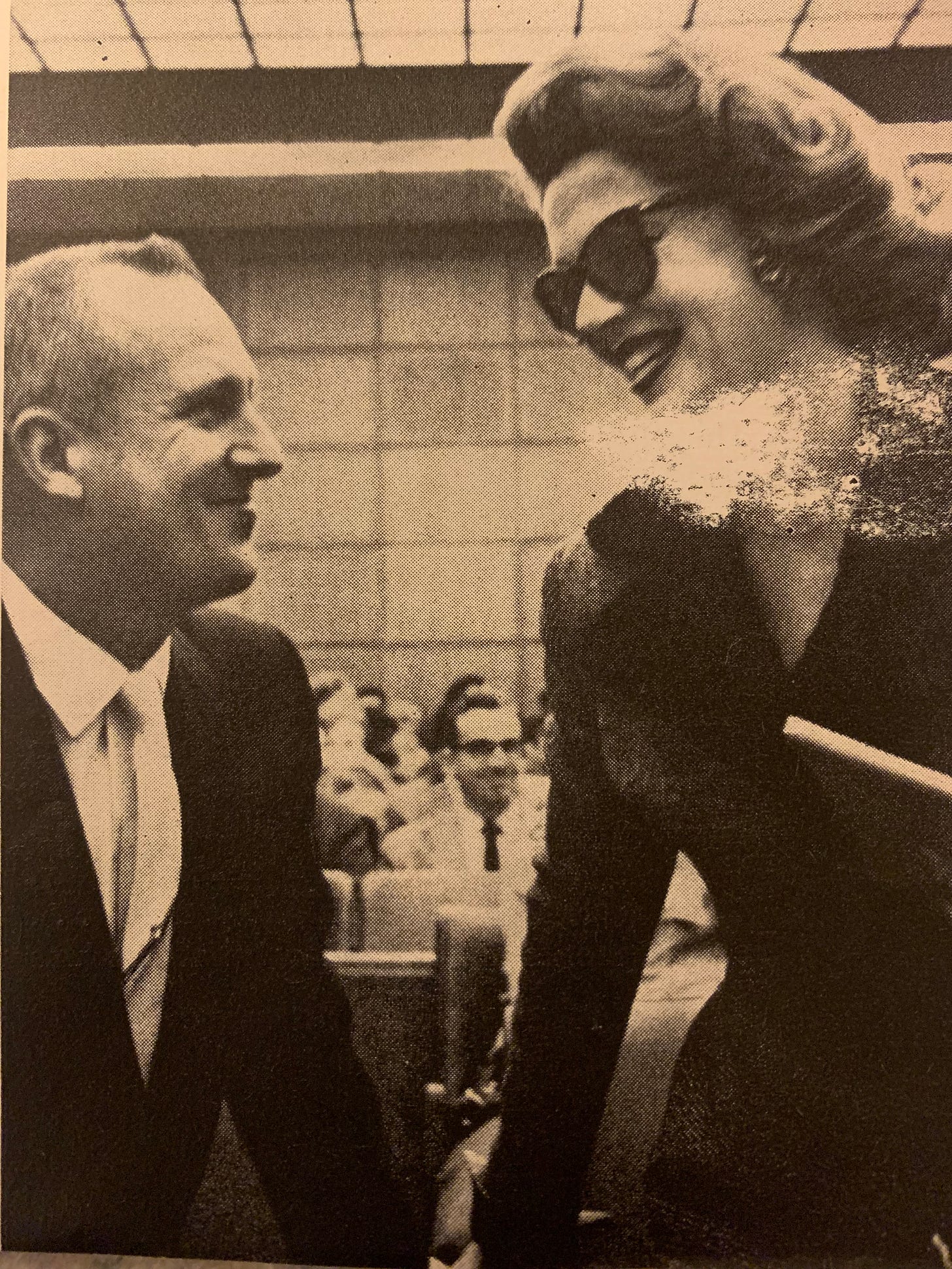

Even the two principals often seem unaware of the gravity of the occasion. Dr. Finch has spent much of his time in court relaxing, smiling nodding his approval as defense attorneys made their points. He is lean and tanned. The eyes are alert and intelligent. His manner is forthright. “Call me Bernie,” he says. The accompanying grin is muscular and confident.

Carole Tregoff is 23 and startlingly pretty in full face. In profile things are not quite so good. The jail diet had put a few unnecessary pounds on her hips, but she is believed to be doing something about getting them off. In the meantime she walks in and out of court with a vaguely seamanlike roll. The smiles that she exchanges with her Bernie are fondly demure. The pair of them are a little like newlyweds separated for the first time by different bridge tables.

Finch would ultimately be convicted and spent 12 years in prison, much of it at San Quentin playing tennis, before being paroled in 1971 and moving to Missouri to start a new medical practice. Tregoff was released after eight years, changed her name and apparently supervised the medical records department at a California hospital. Tregoff never left the area, continuing to walk through neighbors’ gossip and visiting the same hair salon into old age.

They never reunited.

Three quick things about hiking trails

Building a hiking trail is part psychology, part science. Designers aim to build sustainable trails that blend into the local ecology and provide a natural path without disrupting the environment. If only it were so easy. Planners try to anticipate areas where hikers will take shortcuts, or walk off the trail to get around hiking traffic ahead. The solution is to direct routes through boulders, along steep terrain and, most importantly, design thoughtful switchbacks so that tired hikers don’t walk straight down a mountainside. “You’ll lay it out, you think you’ve done it well, and then they make a shortcut and you’re like, ‘Damn, why didn’t I see that?’” as one expert told the Wall Street Journal in 2015.

The best trails are modernized versions of indigineous paths. A lot of today’s hiking paths were once Native American trade routes (just look at Mount Rainier). The upgrades are typically overseen by the National Parks Service or a local land manager, who rely on small communities of volunteers for maintenance. “With federal budgets so tight and 200,000 miles of trails in the U.S., land managers can’t maintain trails using work crews,” Wesley Trimble, communications and creative director for the American Hiking Society, told me. Community members might engage with local conservationists or the zoning board to get a new project done. Or, they might spend 10 hours on a weekend moving felled trees. “It’s a critical part of maintaining access to public lands,” Trimble said. “It’s critical to see a rise in volunteer numbers after the pandemic, when participation has been much lower.”

Trails are getting busier — and that’s good. “The outdoors hasn’t always been equal to everyone, so some of the work that we’re doing has been to change the idea of who’s a hiker,” Kinda Ramos, director of communications for the Washington Trails Association, told me. After more people experienced the outdoors for the first or second time during the pandemic, organizations like WTA are trying to keep up the momentum to use “that energy and figure out how to use that for our community and the better of our country.” Legislation like the Great American Outdoors Act could help. The regulation allocates $1.9 billion for overdue maintenance and critical upgrades through the National Parks. It also makes way for an expansion in who can access public lands. “It’s a chance to give folks a path to nature that they might not have known was possible before,” Ramos said.

recommended reading

Why Buffalo is a hub for illegal debt collectors who scam thousands across the country: Amazing investigative story detailing how Western NY emerged as "a veritable Silicon Valley" for illicit debt collectors tied to organized crime. [@TheBuffaloNews]

The fall of the King of Squirrels: "Phan Huynh Anh Khoa capitalized on Vietnam's digital development — and Facebook's negligence — to build a wildlife trading empire." [@AshLampard]

Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal Omits Big Climate Measures: The president's next infrastructure bill, an idea already floating around Washington, could already be his last chance to pass meaningful climate legislation. [@CoralMDavenport + @LFFriedman]

No More Normal is an every-so-often newsletter by me, Jeff Stone. You can support by subscribing, sharing or suggesting ways to improve.

Barbara Finch wasn't found dead in the garage. She ran away down the driveway running towards the in law's house and Finch chased after her and shot her in the back.